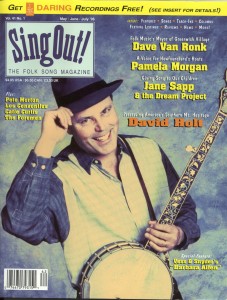

Sing Out! May/June/July Vol.#41 #1

by Dan Kedding

David Holt is a storyteller, musician, collector of old songs and stories, television host and all around nice guy. His T.V. program “Fire on the Mountain” was a celebration of old time and folk music that introduced our musical heritage to a wide and varied audience. He currently hosts “Riverwalk: Classic Jazz From the Landing” that combines traditional jazz music with his stories of the legends of this American music.

David has been nominated for a Grammy and has won the Notable Award from the American Library Association. He has recordings, a video and a book he edited with his friend Bill Mooney, Ready to Tell Tales that was released by August House in 1994. He is a three-time winner of the Frets magazine poll as “best old time banjo player”. David was also selected in 1984 by Esquire Magazine to be included in its list of “Men and Women Who Are Changing America.”

David moved from his native Texas and settled with his family in Southern California when he was in junior high school. He attended the University of California in Santa Barbara and soon after began his lifelong odyssey collecting, learning, and presenting the songs and stories of the southern mountains. In 1975 he founded and directed the Appalachian Music Program at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, N.C., the only program where students study, collect and learn the traditional performance arts of the southern mountains.

David Holt tells stories, he sings songs, and the best part of that equation is that he really enjoys himself and so does the audience. I first met David at a ghost story concert we did together with storyteller Janice Del Negro at the Fermi Lab in suburban Chicago. At dinner afterwards I was struck not only with David’s knowledge of old time music and the mountain tales but also with his complete respect and admiration for the people who had gone before him and the folks from whom he had collected many of his pieces.

Our paths have crossed several times since though usually only for a few minutes to say hello and catch up on each other’s news. This past fall though we performed together at the Northern Appalachian Storytelling Festival in Mansfield, Pa. (one of the finest storytelling events anywhere) and had time to take a walk, do a little antique shop hopping (David knows his washboards!) and to sit down for an interview.

Dan: How did you achieve the marriage of stories and songs?

David: I moved to North Carolina in the early seventies to learn traditional banjo and to collect music. As I was going around collecting music, there was always some little tidbit about the song. I began to use those stories in concert and realized it made the audience more interested and gave them a reason to care about the music and about me. I started telling things about myself as well. I think with any performing, one of your main goals is to give the audience a reason to care.

I didn’t really think about form in stories until I came across two stories. I heard about the elephant that was hanged in Irwin, Tennessee, in 1916. I said to myself, “What? An elephant was hanged?” So I went to the newspaper and got the old articles from 1916 and put together the story. I told it at a concert and it let the audience totally bummed out and angry with me, the teller! But, it also made me realize the power of storytelling.

I had a banjo student who told me about some man who lived in Rozman, North Carolina who made a telephone from his house to an old woman’s house by taking a ground hog hide and tacking it to his window pane, taking a wire, putting it in the middle and running it half-a-mile down the hill to the old woman’s house. She also had a groundhog hide tacked in her window. From that anecdote, I made the story of the hogaphone. I started telling that story. I thought to myself, this is incredible stuff! You can hold a person two-to-three minutes with a song, but with the images of a story you can hold them for fifteen. That was really fun.

So, that’s how the mix of music and stories came about–by collecting the songs and then finding the traditional stories and making some of the stories out of anecdotes. Then I was invited to the National Storytelling Festival in 1970. The revival of storytelling was just beginning. I had never met anybody who called themselves a storyteller. So I started using the musician-storyteller idea.

Many years ago, in the mountains of western North Carolina, there was a young couple named Ross and Anna. They were just sixteen years old when they decided to get married. Ross’ father gave them sixty acres of mountain land. It was steep land, and Ross had to walk all over that sixty acres just to find one flat place. The best place he found was a large flat granite rock that stuck out over the hollow. In the center of that rock was a hole about the size of a man’s fist that went straight down, deep into the rock. It looked like a great place to build a cabin. They could center the cabin right over that hole, and they would not only have a granite floor, but they would have a drain hole in the center of their cabin. Everybody in the community got together and helped Ross and Anna hew the logs and build a beautiful one room cabin.

Dan: Everything you do musically is basically traditional.

David: Something I’ve collected and usually had contact with.

Dan: You don’t usually play pieces that are penned by others or your own songs.

David: I do write songs and know a lot of other people’s songs, and I occasionally perform them. But what I really love–what I feel is my calling–is to collect, present, and perform traditional songs from the southern mountains.

Dan: As we approach the Twenty-first Century, what do you see as the relevance of traditional songs in our lives? Why are they so valuable?

David: I think that they contain more wisdom than we know. The same as with stories. I feel that these old tunes are old mantras, little bits of wisdom that people have put into a musical form. By playing an old tune over and over, which is what we do in traditional music, you’re putting some kind of ancient wisdom through your body. Sometimes, like with Soldier’s Joy or Arkansas Traveler, its a very positive, uplifting kind of thing and its a very happy view of life. But, there are tunes like Frosty Morning or Wayfaring Stranger, that have another message that they are sending through your body. For me, they are like a mantra–an old wisdom that can only be put into music. You cannot put the meaning of Frosty Morning into words, its wisdom is locked in the tune.

Dan: We agreed the other night that in the sixties and seventies we were performing to the converted, and now we are not. It seemed that the audience in Mansfield (PA) held a lot of people who hadn’t heard claw-hammer banjo or slide guitar. How difficult is it to get a modern audience hooked on old-time music?

David: I came of age in the sixties. I am of this world, I’m a modern person, but I love old-time music and traditional stories. I feel as if my goal is to join those two and bring the music forward so it isn’t antiquated. I came to the southern mountains to learn it as a real thing, not as a dusted-off piece from some museum. I learned it from people who were actually playing it. Many of those people have passed away, but the music survives in younger people in the mountains. It is important to me to take the living energy of the music and carry it forward. It’s not easy to communicate this to an audience, that I want to make a living playing the same music some of my old-timey friends played some fifty or seventy-five years ago.

I do believe the music still has relevance, the stories still have relevance. It’s my job, as the presenter, to find the very best songs, the ones that people can relate to, that have good rhythm. To me, rhythm is the basis of everything. They also have to have good melody, good words, then I put it in a setting that allows people to take it into their lives, today.

I know hundreds and hundreds of songs, but I’m probably working from a performance repertoire of maybe one hundred that I know will work. For some of the more difficult ones, the subtle ones, it is my job to give the audience a reason to care about them. That’s where the stories come in. I have to also give them a reason to care about me as a performer, so I don’t lecture to them because they don’t want to hear that. They want to be entertained. But I’ve discovered that to get people to think is entertaining as well. You don’t always have to be funny. The audience never knows where it’s going to come from. I have tremendous variety because I like to keep them guessing as to what’s going to come next.

The day of the wedding came, and everyone in the community came out for the wedding, they had a wonderful time dancing and singing. After the wedding, they had a “pounding” for Ross and Anna. This was an old custom where everyone would bring a pound of whatever a young couple would need to get started in life.

A pound of meal, a pound of lard, a pound of sugar, a pound of salt, a pound of meat. Ross and Anna took their goods up to the cabin, put them on the shelves and settled in.

Dan: Since you perform both traditional music and stories, what do you see as the differences and similarities between the art forms, the audiences, and the presentations?

David: When I learned the songs, people were telling the stories that went along with them, telling about them and where they came from. The mix of music and storytelling was a natural thing for me. I really don’t find much difference at all. The songs and tunes work on a different part of the mind and a different part of the heart than the stories. They are so complimentary–that’s the beautiful thing! I think traditionally there have always been stories and songs together.

Dan: You are not afraid to use technology, though. That’s what I think is exciting about your performances. You are doing traditional music AND you have thunderwear! Tell us about it.

David: I don’t really care anything about technology. None of my instruments are electrified. But, my dad was an inventor and so I’m always inventing. I have a pick that goes both ways. I designed this banjo with a really deep pot for a certain sound that I wanted. Since most of my music comes out of rhythm–I started as a drummer–I love the hambone rhythms, body slapping. From that, I began to think, why couldn’t you take those slapping rhythms and put drum triggers on a suit and play that suit through a drum machine to get modern drum sounds. That was the genesis of thunderwear, a body-slapping suit. I always try to present it as an extension, the most modern extension, of the most primitive form of music. To me, somehow, it fits.

It was kind of cold, end of the winter night, and Ross built a big roaring fire in the fireplace. He could see how wonderful that stone floor was going to be, because the fire began to heat up that stone and fill up the cabin with warmth. In the middle of the night, after they had gone to sleep, the fire burned down, so Ross got out of bed to put some more wood on the fire. He’d gotten about halfway across the floor when the cabin was filled with a sound like, chchchchchchch. Anna heard him scream and hit the floor. The last words she heard him say were, “Don’t get out of bed!”

Dan: Tell how you went from being a drummer to being a performer of about a dozen instruments.

David: When I came to the southern mountains, I really had only one intent, to learn to play claw-hammer banjo as well as I possibly could. Luckily, there were some old-time fiddlers, Byard Ray and a guy named Tommy Hunter, living around Asheville, North Carolina, which was my home. They would sit and teach me the old fiddle tunes note-for-note on the banjo. I wanted to get them just right, clean, but still coming from a drummer’s aspect. I wanted the music to have a lot of drive. Then I began to find all these old-timers that no one was collecting from. They played all these weird instruments, like the bottle, paper bag, jaw harp, bones, washboard, slide guitar, ukulele. I hadn’t realized that music existed. So, I began to learn these things because people were willing to show me and encourage me.

When I was doing concerts for audiences that didn’t know anything about traditional music, I realized that having different sounds was enough to hold their interest. I found that these odd instruments were useful to me in performance as well. Since my basic love is rhythm–the banjo is basically a drum with strings–I love the rhythm instruments. The audience responds to rhythm on a very basic level. You pull out a paper bag, some spoons, and you make an immediate connection with your audience. It’s like saying, “Hey, you don’t need this $3,000 instrument. Look at this!” It is also a challenge for me. When I play the harmonica and the paper bag together, that’s a very hard thing to do, and I get it right! It is not a gimmick, it’s entertaining. And, I’m trying to make them sound as musical as every molecule in my body can make them.

Dan: What drew you to the banjo?

David: When I first came to the southern mountains in 1969, I was traveling with a friend named Steve Keith. He was an old-time banjo player. We traveled all through the mountains going to fiddler conventions and visiting the houses of people who played music way back in the mountains. Everywhere we went people just threw open their doors when they heard that banjo. They’d say, “Come on in and stay a week!” I had never seen anything like that in my life. The sound of the old-time banjo, combined with the unbelievable opening that people gave us, made me want to learn to play. Then, I found the very same thing happened to me. I was kind of a shy person, but this banjo would just open peoples hearts. “I love that sound, what is that?” If they knew it, they wanted to hear more. If they didn’t know it, they wanted to know what it was. I just fell in love with the instrument. Even though I play a bunch of things, the banjo is still the one I never get tired of playing or hearing.

Dan: There are only a few people who have melded music and storytelling–you, Gamble Rogers, Heather Forest, Bill Harley. Why haven’t more people gotten into this?

David: I think that luckily people are using their heads and not getting into it unless they play the music pretty well. It really pains me to see someone pick up on instrument, a little dinky autoharp or something, and just try to add something to a story, because it usually doesn’t! It’s like adding a puppet. You don’t need a puppet, you don’t need an autoharp. Get it out of there! If you can’t tell the story without it, forget the story. But, if somebody is already a good musician, it just flows together. I guess I can’t answer why more people aren’t doing it, but I guess it is good that they aren’t.

The next morning some of their neighbors came to see how they were doing. They knocked on the door and got no reply. They knocked a little harder and they heard that same sound inside, chchchchchchch. They put their ear up against the door and they heard sobbing inside.The door was barred from de so they couldn’t open it.They found a log that was left over from building the cabin and rammed the door. The door flew open and the site that met their eyes was unbelievable. There was Ross in the center of the floor and stone cold dead. There were rattlesnakes writhing all over his body and the floor around him. They could see right away what had happened. The fire had heated up the rock and those snakes must have been hibernating inside the rock. They came up when they felt that warmth and filled up the cabin. They had to get Anna out. They climbed up the side of the cabin and ripped off some of the shingles. One of the men tied a rope around his waist, they lowered him down into the cabin and he put his arms around Anna and brought her out. The only way they could get Ross’ body out was to lasso and try to throw it around his foot as they stood at the door. They caught his foot and dragged his body out.

Dan: When the audience is walking out the door, what do you want them to remember about you? What idea should they return with to the real world?

David: I want them to go away, first of all, feeling that we are together as a group. Something I really love to do at a concert is bring the audience together. I build the thing, block-by-block, so that they go out feeling good about themselves, feeling good about me, feeling good about the music. By the end of the evening there’s something powerful that has happened. If I’m performing for families, I want the kids to go away saying, “That traditional music stuff is pretty good. The banjo, that’s cool!” I want the adults to go away thinking, “There’s something that I learned there.” To me, that’s the joy of putting on a concert.

I feel that traditional music is like an infection. Certain people hear it and say, “I’ve got it, I’ve got to get that, I’ve got to learn how it’s done.” We have to spread this music wide and far because you can’t expect everybody to get into it. I wouldn’t even want to see that. But certain children, certain young people, certain adults will be infected and say, “I’ve got to get more of that!” If it’s spread far enough, we’ll cast enough seeds so that it will begin to grow and will continue on. It is important to me to see that it will continue on because I believe it does have something for us, some wisdom and some roots that we can reach back on when things get really scary in this world. I think that is what the music was about in the past, and that’s what it can still do.

Dan: What do you stress with kids in a show?

David: Fun. I want them to have fun! I want them to come away saying, “I like that guy. I like that music. I like those stories.” I want them to think two things. “Music and stories are really interesting. Maybe I can do it!”

Dan: Your stories are finely crafted. What’s the process you go through to get them there?

David: Originally, it was always telling, then telling, then telling. Making sure that the story was building, going somewhere, and that it had a very clear ending. That’s very important. We, as humans, need closure. Now, I can take a story and think it out almost on my feet.

They had a funeral for Ross and everyone in the community came. After the funeral they talked about what should be done about the cabin. They decided that the best thing to do would be to tear it down and rebuild it next to Anna’s parents so she would have a place to live. They went up there the next day but the snakes were still all over the floor of that cabin. They decided to wait a week but when they came back it seemed like there were more snakes still coming out of that hole as spring approached. They waited two weeks. When they got back the snakes were all around the cabin. They couldn’t get close. It troubled the people so deeply they decided that they would destroy that cabin. They lit it in fire and burned it down. And that’s the end of the true story of Ross and Anna and their house of snakes.

Dan: Are the books fun?

David: It’s a tremendous amount of work and not as much fun as making a tape. But it goes along with my collecting and interviewing people that I like. I enjoy it and will continue to do it, but I like the live performing more.

Dan: Your stories always make the audience feel the humanness of it all. Do you look for stories or do they find you?

David: I keep my eyes open all the time for material–when I hear conversations, when I’m reading a book. I’ve lived a lot in this life. I’ve had a lot of tragedies happen to me, and a lot of good luck. I feel like at age forty-nine I’ve lived two, full lives. So, I believe I can incorporate some of that into what I do, whether its funny or sad. To me, life is pretty mysterious, and there are no easy answers. So, I keep my eyes open for material that highlights that.