A Hand in the Great Legacy

Doc Watson & David Holt at Merlefest 2010- photo: Lonnie Webster

At first glance, it might seem that David Holt and Doc Watson have little in common

Raised in Texas and California, Holt holds a degree in biology and art from the University of California-Santa Barbara. The sixth of nine children, Watson, 87, grew up blind in rural Deep Gap ; he earned his “degree” as a “road scholar,” touring and playing music as one of the most influential guitarists of the 20th century.

But with music as the bridge, the two musicians share a quarter-century of friendship, a Grammy award and the Hills of Home tour, which brings them to Meymandi Concert Hall tonight for a PineCone-sponsored show.

David, Doc & photo of Big Joe Williams

Holt, 64, went to the mountains in the 1960s to study traditional music and culture with Appalachia’s renowned elder artists. He founded the Appalachian Music Program at Warren Wilson College in 1975; and in 1984, the multi-instrumentalist and storyteller hosted public television’s musical variety show, “Fire on the Mountain.” Holt and Watson began working together that year, when Doc and his late son, Merle, were invited as guests on the program.

Since then, the two friends have toured together and recorded several albums, including “Legacy,” which won a Grammy in 2002 for best traditional folk recording. The three-disc project features tales and songs that help define and offer insight into Watson’s storied life.

“I think ‘Legacy’ was done just at the right moment, when Doc was still in his prime but old enough to look back on his life and sum it up the way he wanted to,” Holt says.

David & Doc on Fire On the Mountain (TNN) 1984

The Hills of Home collaboration began in 1998, when Watson and Holt were asked to do a fundraising concert for public television station UNC-TV. The response was so positive that they decided to continue performing together, as their time and schedules would allow. Like the fundraiser and “Legacy” CD, Hills of Home features songs and instrumentals from Watson’s extensive repertoire, and Holt asks questions that Watson answers in his warm, Deep Gap drawl.

“It’s such an intimate evening when you do that,” Holt says. “And I always try to ask him some question that I don’t know the answer to.”

Holt will ask questions about the years Watson spent in Raleigh as a student at the Governor Morehead School for the Blind. There, Watson was encouraged to learn guitar by another student, jazz

pianist Paul Montgomery, who taught Doc his first guitar chords.

“There were lots of wonderful things there and lots of terrible things,” Holt says. “It was a life-changing experience for this little blind mountain boy who had never been anywhere.”

Gaining insight

Working with Watson, Holt has gained important insights about music, and has learned intimate details about how the older man approaches his life and his songs. While never allowing blindness to hinder his ambitions, Watson has transformed his disability into an asset that guides and informs his muse.

“One thing I’ve learned from Doc,” Holt says, “is to really listen closely to the tone of each note, to the meaning of each note and the lyrics to the song, and to think about the back story of the song.”

“Doc will take a song like ‘I’ll Rise when the Rooster Crows’ and he will think out every aspect of what is going on in that song: Why the guy is singing it, who he’s singing to, what it all means, what each word

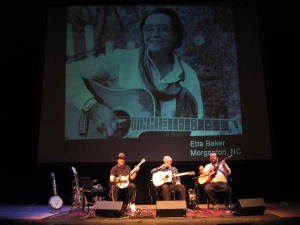

Hills of Home Tour -slide of Etta Baker-2009

means. He has a lot of time to think because he’s not distracted by the visual world. He adds power to his singing and his presentation by really inhabiting that song. He’s deeply into that story:

I’ll rise when the rooster crows/

I’ll rise when the rooster crows/

I’m goin’ down South where the sun shines hot/

Down where the sugar cane grows

“Most people would just sing that as a little ditty. But Doc has thought it out about how this guy has gone up North and he’s dreaming about going back to the South; his girl is back there and his home, and he loves the mountains and the food in the South – he’s thought all this out. He does this with every song.”

Booked until he’s 89

Holt says that, after nearly 50 years in the spotlight, Watson may decide to hang up the old guitar any year now. When he does, the world will lose a musical genius who leaves a legacy as rich as any of our nation’s folk heroes.

“[Watson is] booked up to his 89th birthday,” Holt says. “I think he’ll just go until he can’t do it. That day can’t be that far off. I feel that each of these concerts, for me, is really special. And I think for the people who see them, too.”

Doc Watson and David Holt